The Danish agronomist Gunnar Søndergaard was yesterday elevated to Commander of the Most Admirable Order of Direkgunabhorn, which is the highest possible order for a non-Thai person to receive. Gunnar Søndergaard has already previously received the Order of the White Elephant.

The Most Admirable Order of the Direkgunabhorn is in Thai language เครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์อันเป็นที่สรรเสริญยิ่งดิเรกคุณาภรณ์.

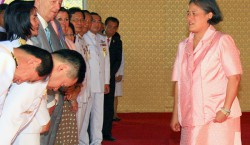

Gunnar Søndergaard received the order in person from Her Royal Highness Crown Princess Sirindhorn of Thailand at a ceremony at the Thai-Danish Dairy Farm, which he helped establish in the 1960’s. His achievement in making this dairy project a success is also the reason why he received the honour. Before the Thai-Danish Dairy Farm was established, some milk was produced based on Indian cattle held in dark and fly infested stables. A few less succesful projects within the dairy sector had been attempted as well producing recombined sweetended milk based on imported milk powder..

It was the farm paid for by the Danish Agricultural Promotion Board and the related projects in Muak Lek some 140 km north of Bangkok that in a comprehensive way brought modern dairy technology to Thailand, paid scholorships for Thai dairy technicians to be trained in Denmark and made Danish genetic material the foundation of a new, high yielding milking cow stock in Thailand.

Today Gunnar Søndergaard is 83 years but still physically and mentally fresh. He had come to Thailand to receive the Order together with 17 members of his family. All of his four children were born during his and his wife’s stay in Thailand – all except one was even born in Thailand – and apart from sharing the honor with their father, the occasion was also an opportunity for them to visit their childhood home.

The Danish Farm

The idea to establish the farm came to Gunnar Søndergaard during the years when he worked as a swine breeding expert for FAO in Bangkok from 1955 to 1959. In this capacity he had travelled all over the Kingdom.

“I couldn’t help noticing how cow milk was simply not available in Thailand,” he recalls.

“In the big cities you could buy sweetened condensed milk produced from milk powder but the total consumption was at that time only 1,3 kg milk per Thai citizen per year. In comparison, this figure is today 13 kg milk per Thai citizen – but in Denmark it is today 90 kg per capita per year,” he adds.

Gunnar Søndergaard didn’t believe what many experts said at the time, that Thai people could not digest milk. When he was transferred back to Copenhagen where he worked at the National Research Institute on Animal Husbandry, he brought the dream with him that it should be possible to establish a dairy farm in Thailand.

He proposed the plan to the Danish Agricultural Promotion Board. The Board agreed and send a three men team including Gunnar Søndergaard to make a feasibility study and look into the project in more details. At the time, the Danish development assistance organization Danida was not yet established, so it had to be this semi-official body owned by the Danish farmers associations, that established the farm. Then things moved fast.

In January 1961 the team concluded that it was indeed feasible and in October 1961, an agreement was formally signed with the Livestock Department of the Ministry of Agriculture to be partner in the project. Gunnar Søndergaard became the first Danish Director of the project. As his Deputy Director he had handpicked a veterinarian friend he knew from his swine breeding days, Dr Yod Vadhanasindhu, who worked at the time in Chiang Mai.

The department had three optional farm locations to offer – one closer to Bangkok, but down in the lowland, one in Muak Lek and one further up north in Pakchong. Gunnar Søndergaard found the Muak Lek location was the best. It was close to the market in Bangkok and still it was up in the relatively cool mountains. The Livestock Department then started clearing the land, which was dense jungle at the time.

“I still remember crawling under the foliage up the hill trying to imagine if this would be a good place to build the farm,” Gunnar Søndergaard recalls.

Ready for Royal opening

“I made the drawings of the farm buildings myself,” Gunnar Søndergaard continues.

“But because we wanted to be able to be ready for opening when King Frederik and Queen Ingrid were coming on a visit to Thailand in 1962 we asked Christiani & Nielsen to do the construction.”

The Danish Christiani & Nielsen was at the time one of the most advanced engineering and building contractors in Thailand and specialized in tight project management. There were problems getting some of the equipment up to Muak Lek because the rather narrow road to Bangkok was flooded, but eventually the construction could start on 10 December 1961 and on 16 January 1962 when King Frederik and Queen Ingrid arrived accompanied by King Bhumibol of Thailand, the stables were ready to be inspected and declared open.

“The road was still flooded, so their majesties had taken the train to get from Bangkok to Muak Lek,” Gunnar Søndergaard recalls.

“Next, we needed to have some grass ready for the cows to come. I sent in a truck to cut grass along the canals in Bangkok and this we ploughed slightly into the soil on the cleared fields. The grass would then set roots from the knees and quickly grow up. In Denmark we sow grass, but this is the Thai way,” Gunnar Søndergaard explains.

Later in the year 1962 the first 39 red Danish milking cows came from Denmark, together with a red Danish bull. At the same time, Gunnar Søndergaard bought 378 small local Thai cattle and started breeding a mixed stock using sperm from the red Danish bull to inseminate the Thai cows.

“I knew from other experimental farms that the foreign imported cows would not live long in Thailand with the tropical diseases they would catch, but I wanted to produce milk from the beginning,” Gunnar Søndergaard says.

In 1963 he bought another 257 cows from Indian dairy farmers in Bangkok. They were also inseminated with sperm from the Red Danish bull. Later that year, another 50 Danish cows arrived from Denmark, but none of them lived long either.

“The newly bred, mixed cows, could produce 37 pct of the milk that at Danish cow would produce. This would increase when the cow was attended to by only the same farmer or if the calf was placed by the udder of the cow – then it would lay down more milk,” Gunnar Søndergaard explains.

Dirty Danish milk

During the first couple of years, it turned out to be an unexpected problem to sell the milk. It was rumoured that the milk was full of bacteria although the cows were actually washed twice a day – more than needed anywhere else in the world.

“Eventually, however, one shop in Bangkok started selling the milk – and as the customers soon flocked to the place, suddenly the situation was reversed. Now, the shops would come to us and ask if they could be a reseller,” Gunnar Søndergaard recalls.

Actually, it was not initially planned that the project should include a dairy plant. The milk was to be delivered to an existing company for processing, but as they didn’t pay for the milk, the board had to re-think and establish their own dairy plant which packaged the milk in plastic bags.

Training

The core idea with the farm was to train Thai farmers producing milk and when they had been trained they would be given a farmland near the Thai-Danish Dairy Farm in Muak Lek. That way the production in the whole area would grow and a modern dairy could be sustained with a steady and large milk supply in the area.

Søndergaard sent a man to visit all the agricultural schools in Thailand to pick out students for the one year training program at the new agricultural school in Muak Lek. The young potential farmers had completed 6 years of primary education and three years at a Thai agricultural college, before they came to the farm.

“But they didn’t know much about farming in real life, so the first three months we sent them into the field to be taught hands on the basics about farming by our instructor. It also had the effect that half of them quit and only the dedicated hard working trainees were left. Then they were allowed into the stables to milk by hand after having trained for several days to milk properly by hand on rubber udders. Only when we saw that they were good at that, they were allowed to use the milking machines,” Gunnar Søndergaard chuckles.

“They had to work hard and were only paid 10 -12 baht per day!”

Some of the students were later given scholarships in Denmark and although some of them even decided to stay in Denmark after their scholarships ended, most of the students returned dutifully to Thailand where they were offered to buy cheap farmland around the dairy where they could start their own milk production. The farmers delivered their milk to the dairy plant and continued to receive guidance, courses and veterinary treatment from “The Danish Farm”.

Today, many of the students from the 1960’s are managing directors in the Thai dairy sector.

A job well done

In 1971, the Thai government took over the responsibilities, and the project was organized under the management of a newly established enterprise named “The Dairy Farming Promotion Organization of Thailand” (DPO). Gunnar Søndergaard’s job was done. His replacement as Director became his counterpart over the many years since the project was established, Dr. Yod Vadhanasindhu.

”After almost fourteen years in Thailand since 1955, I also felt it was time to return to Denmark,” Gunnar Søndergard reflects.

”My family had grown to include our four children, Tyge “Boyse”, Bendikte ”Diddi”, Sune “Ki ngua” and Turid “Sussi”. My wife Ruth had given birth to all of them – except Sune – in Thailand. If they were to attend Danish school it was about time!”

More postings

Gunnar Søndergaard and his family didn’t stay long in Denmark, though. Malaysia had noticed the remarkable success of the Danish farm and Gunnar Søndergaard went to Malaysia on a four year contract to repeat the success.

”But the Malaysians misunderstood the concept. Instead of setting up training facilities, they wanted to have large government dairy farms. It was a different approach and the project not successful.”

After working in Malaysia Søndergåard got a job as adviser in Tanzania, where some of the large dairy farms had recently been nationalized. The job was to help these farms located on the foothills of Kilimanjaro.

“The location was beautiful, but I did not like the corrupt system” he says bluntly.

From Tanzania the family moved back to Denmark. Here Ruth was diagnosed with cancer and died after a short battle with the disease.

After two years in Denmark, Gunnar Søndergaard was given another posting in Kenya as agricultural consultant for the private sector. This was a two year posting which was cut short because a member of the Danish staff at the Danish Embassy in Kenya.

”He engaged so fiercely in an argument with the Kenyan head of the department with the result that my project was terminated and I had to return to Denmark. I don’t know what he wrote in his report, but I am quite sure that he blamed the whole incident on me, because that was the last Danida posting I ever got,” says Gunnar Søndergaard.

”Even when the DPO contacted Danida and requested them to send me on an assignment to Thailand, Danida chose to send another person.”

Correcting the myths

Looking back, there are two myths about the Thai Danish Dairy Farm, that Gunnar Søndergaard would like to set straight for the record. The first myth is, that the Thai Danish Dairy Farm was established by Danida.

”Tthe fact is that Danida was not created in 1961 when the farm was built. Danida was not established until two years later in 1963. Danida first came into the picture in 1966, when we started sending young Thai dairy students to Denmark – at that time we were already successful,” he states.

Gunnar Søndergaard adds, that he has tried to correct the text on the website of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which contains this information, but the misinformation remains in place.

The other myth is, that the Thai-Danish Dairy Farm was established on the initiative of HM King Bhumibol of Thailand.

”The true story is as mentioned above. The project was suggested by me and created with the support of the Danish Agricultural Promotion Board and with the Live stock Department under the Thai Ministry of Agriculture as the local Thai partner,” he states.

The inauguration of the Thai Danish Dairy Farm on 16 January 1962 by King Frederik IX of Denmark and King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand remains, however, a revered historical day for Thai agriculture. Every year in January, a Dairy Fair is held on the grounds of the Thai Danish Dairy Farm. The fair includes both a technical exhibition for suppliers to the industry and booths with products from the many dairy plants that has followed in its footsteps – and today also an increasing number of fun and entertaining events based on the cowboy theme.

It was during the Dairy fair this year, that Gunnar Søndergaard was awarded the Most Admirable Order of the Direkgunabhorn.

Participating in the ceremony was also the Danish Ambassador and wife Mr Michael Sternberg. Next month, Gunnar Søndergaard will be back in Thailand to receive an honourable doctor degree from the Maejo University in Chiangmai.