Many international aid organisations have left the old war-torn country infested with explosive remnants in favour of urgent cases. But one of the organisations still standing strong in Vietnam, is Norwegian People’s Aid with two Scandinavians in charge.

By Jonas Boje Andersen and Lærke Weensgaard

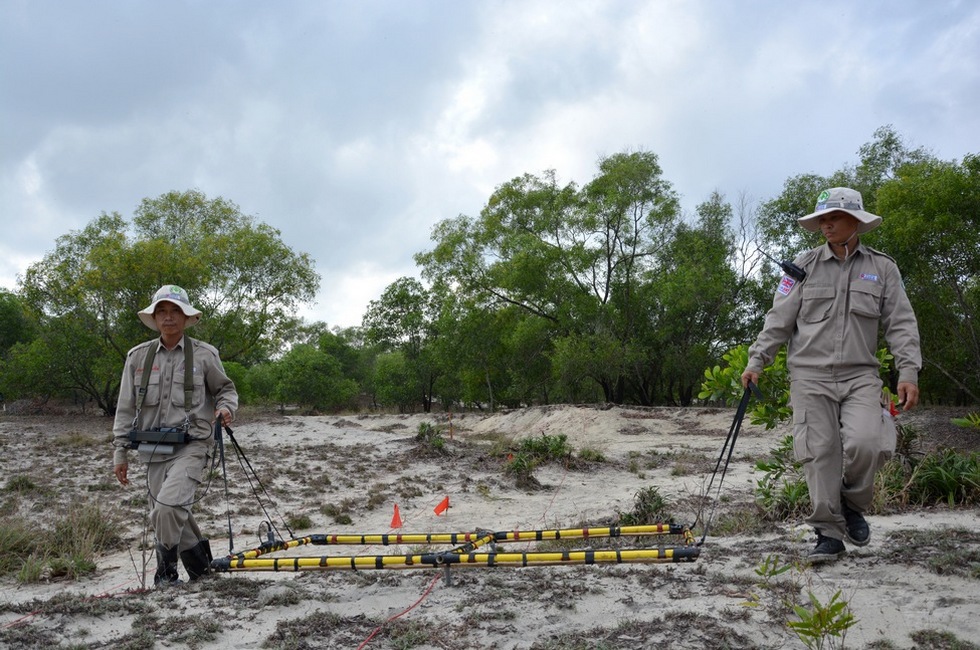

In a vast coastal area in the central and most narrow part of Vietnam, the scorching hot November sun is beating down in the early morning hours. A few farming houses are spread across a landscape consisting of small trees, bushes and sandy ground. Around this bushy landscape, dozens of uniformed military-looking personnel are walking meticulously around with metal detectors. They have been walking since dawn to avoid the worst part of the afternoon sun. They are not here to uncover hidden treasures but to find explosive remnants from the Vietnam War. The job might be dangerous, but the heat and the cost of time do not allow them to wear an armoured suit.

With more than 400,000 tons of submunition dropped by the United States some 40 years ago, Vietnam is still far from being rid of so-called cluster munition. But many aid organisations have left Vietnam in favour of pursuing more urgent cases like Syria and Iraq. One organisation still far from done in Vietnam is the Norwegian People’s Aid, also called NPA.

“It’s naive to think Vietnam will be free for bombs in 100 years. By comparison, we still find bombs from World War II in Europe, but we will need several years to clear the high priority areas in Vietnam,” says Norwegian Jan Erik Støa, Operation Manager for NPA in Vietnam.

NPA started their first mine action program in Cambodia in 1992 and began supporting Vietnam with disposal of unexploded ordnance in 2008. NPA is now one of Norway’s largest NGOs with involvements in more than 400 projects in 30 countries. With classic Scandinavian gender-policies, the NPA has been the first demining organisation in Vietnam to have several all-female teams in their clearance projects. Something that quickly caught the attention of locals and Vietnamese television, if you ask the Swedish Senior Technical Adviser, Magnus Johansson.

He talks as straightforward as he looks. Military sunglasses, a big American Ford pick-up truck with the American and Vietnamese flag side-by-side and with a militaristic disciplined approach to his job. With 14 years of service as an Officer in the Swedish Army and another 14 years in the business of demining at many former battlefields around the world, he is a man with a lot of experience.

In many ways a lot like his Norwegian co-worker Jan Erik Støa. 49-year old Jan Erik Støa started in this line of business for the United Nations in 2001 and a year after for NPA. The former soldiers met in 2004 while being stationed in Sri-Lanka and has since joined forces at various conflict-areas. In Vietnam they oversee the projects for NPA, but prior to that, they also went digging the ground for explosives themselves.

Disciplined work

Today, 50-year old Magnus Johansson is taking ScandAsia out in the field at the shores of Quang Tri province, where NPA is currently working. As technical adviser his job is, among other things, to make sure that the local people is trained and equipped to deal with their dangerous land with utmost caution.

“I’m very fond of being stationed in this part of the world. The Vietnamese are competent and very easy to work with. No drama with them,” he says.

Magnus Johansson and Jan Erik Strøa are both married respectively with a Thai and a Cambodian wife and both have children. Just before their service in Vietnam, Magnus and Jan were in Laos tracing explosives remnants. They both share the same kind of methodology to the work.

“You have to follow rules and be disciplined to work here,” Magnus Johansson says, as the many NPA workers sweeps the ground with their metal detectors causing constant ‘bip’ sounds indicating several unexploded remnants. He adds that it is not a militaristic approach they are looking for when employing workers, but it does demand an enormous thoroughness to avoid accidents.

Two years ago, they tragically had an accident. A freak accident, Magnus Johansson explains. It was just a routine job for one of the Vietnamese team leaders as he was called to inspect a newly discovered ordnance by one of his subordinates. As he kneeled to inspect it, the object blew without even being touched. In their Toyota Landcruiser ambulance, they rushed him to the nearest hospital two hours away, but there was nothing to do. The shattered pieces of metal had caused lethal damage to his chest, and he died on the way.

Luckily these kinds of accidents are extremely rare, and it is the only accident NPA have had in Vietnam, but there is inevitable a risk of doing demining. Now, NPA have employed his son for the same project as a form of compensation, as the father was the families only source of income. It is estimated that Vietnam has suffered around 50,000 casualties in the years after the war due to explosive leftovers in the Vietnamese soil.

Strategically important areas

It is not hard to imagine the battles that took place in this beachy terrain during the Vietnam war with all the places to take cover and the ditches to hide and ambush. You can almost see the American soldiers taking position while the helicopters roar through the sky.

Quang Tri and neighbouring Hue was strategically important places for the Viet Cong and the Americans, as this was where the border between North and South Vietnam went. This was also the place in Vietnam that set the stage for some of the fiercest battles during the war. It was not guerrilla war but traditional battles, that took place here. That is also the reason why in particular these provinces were so heavily bombed, and still to this day demand attention.

According to the Vietnamese Government, Quang Tri is the third worst area when it comes to explosive remnants. If you ask Magnus Johansson, Jan Erik Støa and their team, it is undoubtedly the worst affected province. That also means, that it is all sorts of unexploded remnants they find.

This beachy area hides a lot of bombs fired from naval battleships, but most of all the soil hides air-dropped cluster munition also known as ‘bombies’. Usually, every single container of bombies contained 600 small bomblets. Around 40% of the munition in a container did not explode when it was dropped, leaving some 240 unexploded bomblets on the ground for each container. Especially in the areas where NPA works, it is not landmines but bombies they find, which are dropped in a pattern that makes them easier to find than landmines.

“Those little bomblets look like small footballs which is attractive for small children to kick at,” Magnus Johansson explains.

But it is also very easy for the farmers to accidentally hack in the ground and set a bomblet off. Just a few days before ScandAsia’s visit, NPA had a call from a woman whose 10-year old daughter picked up a large unexploded bomb and brought it to show her mom at their property. NPA has secured the perimeter around it and is ready to dispose it within a few days.

These hazardous situations are luckily more and more rare in Vietnam, partly due to NPA’s risk education in the provinces and partly due to new laws on sale of scrap metal. Jan Erik Støe recounts how he has seen small children with homemade metal detectors and old men stocking bomblets on their freight bicycles to sell it at the local market as scrap metal, when he started in Vietnam for NPA. The metal prices were expensive, and it was something a lot of locals could earn some extra money on.

Steps of NPA’s work

Biiiip. A worker with a metal detector stops. He moves the metal detector around while listening to the sound. Some places the sound fades off, but at one place it gets higher. He places a red flag in the ground next to it and carefully starts to remove the sand. In the ground, he finds a brown and rusty hand grenade.

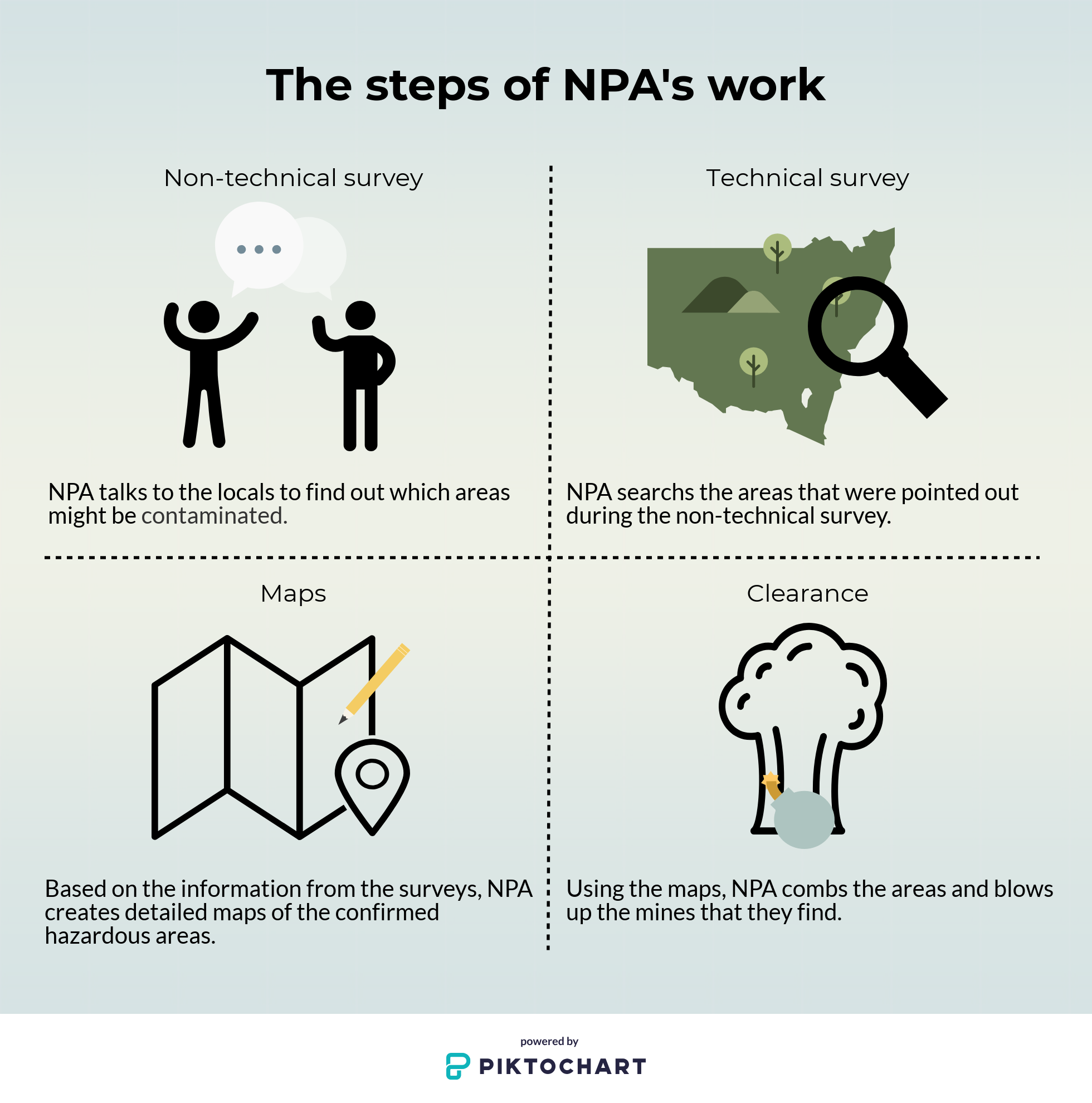

Prior to finding the hand grenade, a long and technical process has taken place. Simplified, the whole process from finding the areas with explosive objects to destroying them can be boiled down to four steps:

The non-technical survey starts when NPA begins to work in an area that have not been searched for explosive objects before. To get an idea about where to start, they send small, mixed teams of men and women out to talk to locals, who have encountered explosive objects.

Once they have an idea about which places can be dangerous, they start the technical survey. It is a systematic way of searching for bombies with metal detectors. In this phase, the goal is not to find every single bombie. Instead, they aim at finding the border of the contaminated area. Once they can separate the contaminated area from the non-contaminated area, they make a map to use in the next phase.

Only now, they can start to remove the bomblets. In this phase, the workers search every centimeter of the area inside their new-found borders. They must find everything down to 30 centimeter in the ground.

Watch a demonstration of how they search:

Almost every day, the teams find explosive objects:

“It is very rare that we have days where we don’t find some,” says Jan Erik Støa.

Two weeks after ScandAsia’s visit, NPA destroyed an US. aircraft bomb weighing 340 kg. The bomb was found by a farmer, when he was about to harvest his land.

On the day of ScandAsia’s visit the catch is smaller. Besides the hand grenade, two more objects appear. Every day ends with the team detonating what they have found during the day.

10 years in Vietnam

The hand grenade is put in a hole with two other explosive objects and sandbags are placed around the hole to control the explosion. With microphones, they warn neighbours or others passing by not to enter the area since they soon will detonate the objects.For an outsider, the upcoming explosion is exciting, but for NPA’s employees it is just routine.

Watch parts of NPA’s preparation for the detonation:

NPA has built up their work routines in Vietnam since 2008 when they came to the country. During those 10 years, the work has developed a lot.

The number of employees has grown from approximately 20 to 280. Among them is the very first female team in Vietnam.

The actual clearance has only recently become a part of NPA’s work in Vietnam. NPA started clearance in Hue province in 2015 with Norwegian funds, and in October 2018 in Quang Tri, when NPA began to receive funding from the United Kingdom. Before that, the clearance has been done by the Vietnamese military or other international NGOs.

Until NPA started to clear bombies, their work revolved around making surveys. Their techniques have become more and more effective over the years and especially the technical survey has changed. When NPA first came to Vietnam, they would search all parts of the areas they suspected could be contaminated, wasting both time and manpower. They changed to their current method, where they search for the border of the contaminated areas and sweep every centimeter during the clearance instead of the survey.

In the ten-year range NPA has been in Vietnam, they have destroyed around 76,000 items of cluster munition and other remnants of war. The work might be moving forward, but there is still a long way to go:

“If we continue to get the funding we need, we expect to be able to leave Vietnam in 15 years. But we do struggle to find enough money,” says Jan Erik Støa while addressing that since the war, the Vietnamese Government have been keener on prioritising funding’s in the tourist-sector and on infrastructure than tracing explosive remnants.

Back in the field, the detonation is almost ready. An explosive charge is connected to a remote control by a long cable. With the remote control and the employees on a safe distance, the only thing left to do is to push the button on the remote control. It is done, and the rusty old war remnants explode.