A Royal Copenhagen vase portraying the little mermaid has been the genesis of this current research. The vase was presented to Tan Heng Soon, the father of my late husband on his retirement as a comprador with the Danish East Asiatic Company at their Penang, Malaysia place of business. As his name indicates, my father in law was Chinese, a Peranakan Straits Settlement Baba. My husband left Penang to study in Australia where we met and married; he went on to be a Maths and Science teacher.

I have been researching aspects of my late husband’s culture and history as a Baba from Straits Settlement Penang and I have always been fascinated with the connection which tied Europe to this Peranakan family in Malaysia. The term comprador is perhaps not well known beyond Asian circles nor the notion that Western merchants relied upon Chinese compradors in conducting business. The word ‘comprador’ is derived from the Portuguese word for ‘buyer’.

A comprador was characterised by a proficiency in English, possessing of business connections, displaying personal trust and playing a special role as mediator. These bicultural middlemen were social leaders, cosmopolitan and their children were Western educated. As such, they fulfilled the role of critical agents in the colonial enterprise. Penang’s colonial society was very cosmopolitan with the advantage of being on the route of the larger Western shipping lines. It quickly became an important entrepot, i.e., a port, city to which goods are brought for import and export, for collection and distribution.

The East Asiatic Company, founded in 1897 by H.N. Andersen, started with shipping and trading, and by 1902 acquired at least one teak forest concession from the Siamese government in Phrae province. The company conducted business under the Danish royal flag, being permitted to fly “ the swallow-tailed flag”, and their records are presently held by the Danish National Archives. As Covid 19 precluded any hope of consulting these archives for the time being I searched for other avenues.

An interesting East Asiatic Company photo album held with Universite Cote D’Azur Bibliotheques and which provides a photographic record of the company’s operations in Thailand in the early twentieth century presented itself and is now available for reference work. The visual record chronicles a trip to Siam and Laos with travellers/personnel linked to both the East Asiatic Company and L’Est Asiatic Francaise, an affiliated company founded in 1902.

The trip starts in Bangkok and travels via Uttaradit north to Phrae, the teak forests of northern Thailand and thence to Laos. The album contains many photos of the people living in these regions. Journeying then by boat, the travellers descend the Mekong using small wooden boats bearing the flag of the French East Asia company. Although the photographer is presently not known, the composition and framing of the images suggest a professional was engaged to record this expedition. A large number of the 352 photographs contain a handwritten copperplate description in English and the archivist at Universite Cote D’Azur Bibliotheques has provided a comprehensive summary together with a mapping of the journey.

Small clues suggest a possible dating of this trip between 1902 ( the founding date of French East Asia) and 1910 ( a photo of the gunboat La Grandiere which sank that year appears in one photo). Further work is ongoing to ascertain a more precise date for the journey.

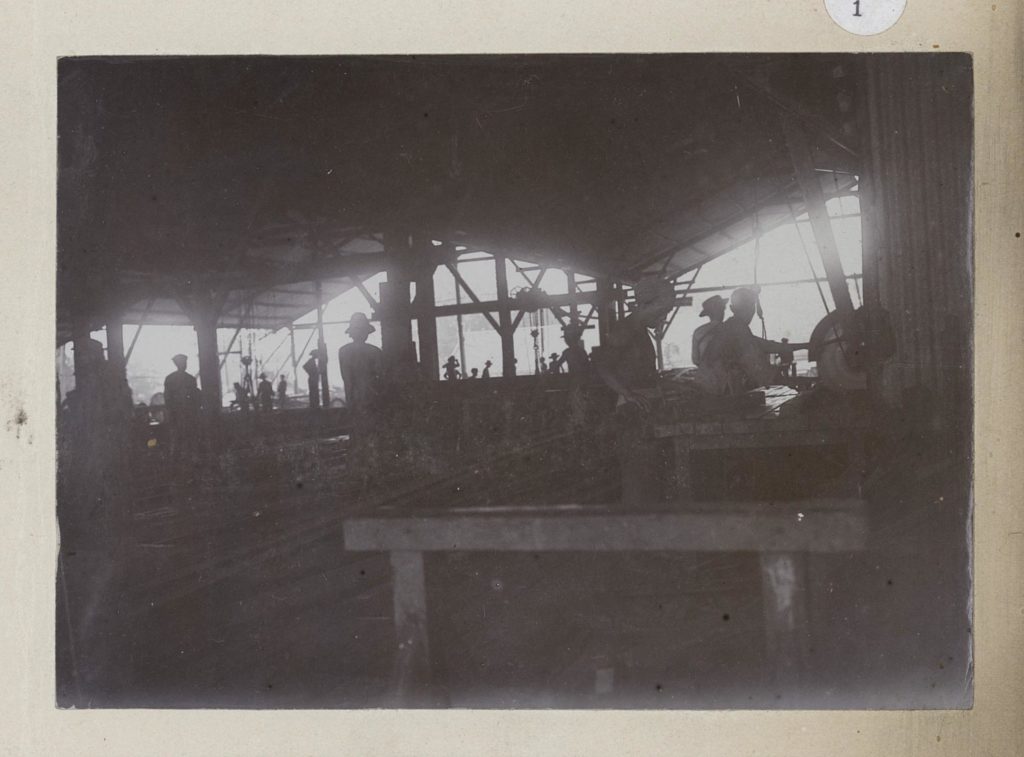

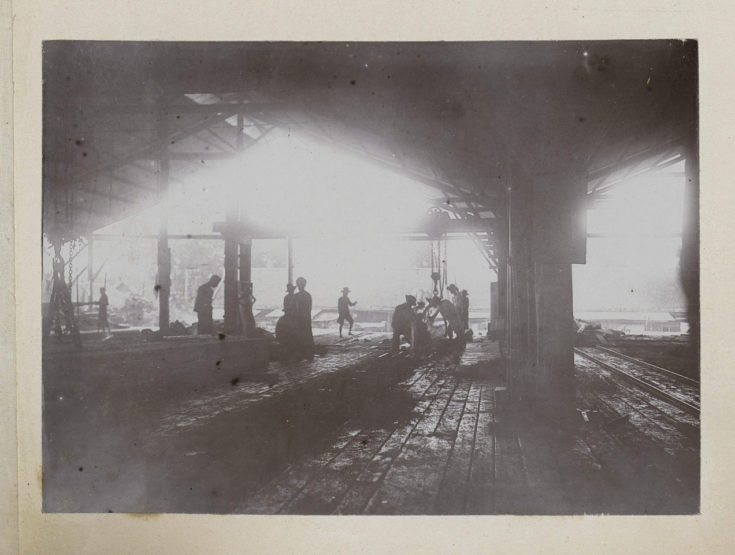

The visual record in the album vividly documents the trip beginning with a series of images of the East Asiatic sawmill in Bangkok. Located on the east side of the Chao Phraya river, wide-angled shots, moody in tone, show the sawmill interior together with a large number of workers. The photos show an extensive sawmill with large sloping roof; details reveal the mechanics of the operation, including saws, pulleys and chains. East Asiatic Company, as with other companies involved in the teak industry, classified the product into quality designations, e.g., premium, Eastern quality, etc. A variety of clothing styles are visible on the workers, suggestive of differing roles. The camera looks outward, toward the wide waterway which teak rafts demanded for transportation purposes. Each sawmill had its own wharf with a crane for unloading logs prior to moving them into the mill.

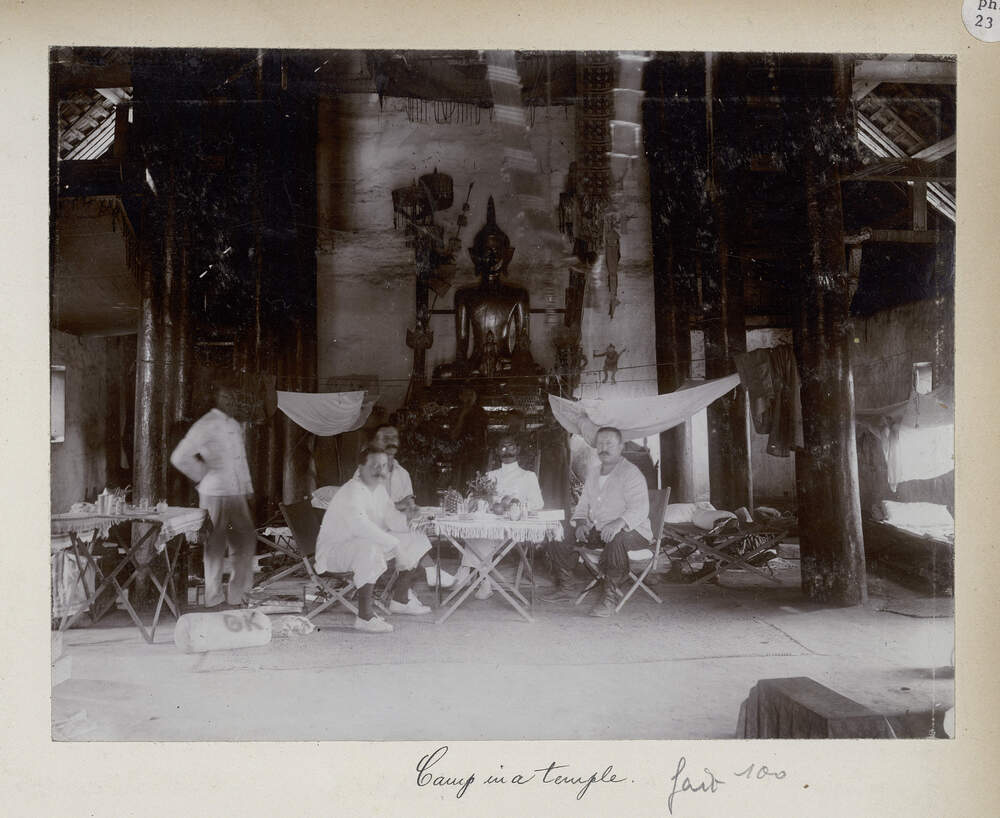

At Phrae, photos capture the interior of the East Asiatic office and European and Thai employees. Social life is recorded with games of tennis and polo together with after-game relaxation when the travellers are seen being served drinks. A particularly evocative image appears as the travellers are framed as they camp in a temple. Formal tables and chairs are set up with beds and camp stretchers all in front of a Thai Buddhist deity. In the foreground is a duffel bag with the East Asiatic company mark in Danish ØK, clothes and nets strung up, pith helmet and two rifles close by.

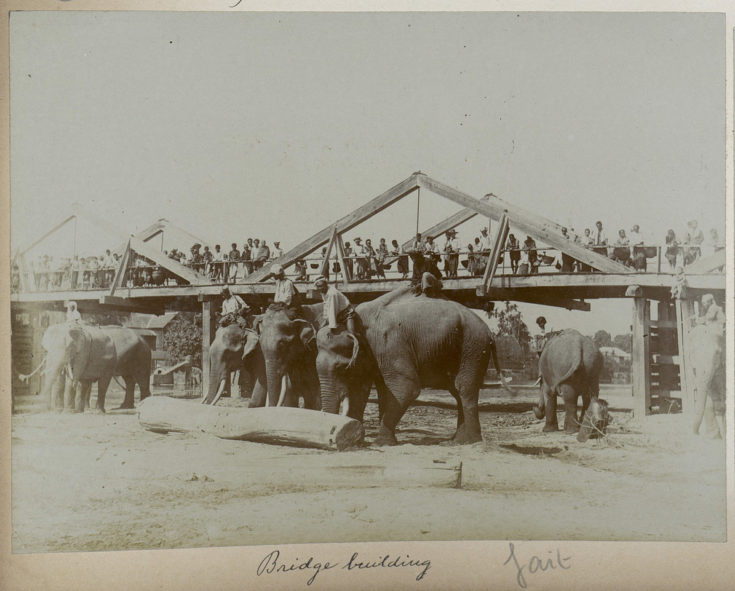

The role played by elephants in the teak industry is well documented in the album. As the travellers set off on their trip we view a large team of elephants with palanquins covered by canvas marked with the company name. Elephants, mahouts plus a large servant retinue begin the expedition north. Daily life is captured with scenes showing elephants feeding, being rested, breaking camp in the morning and loose elephants crossing a creek. One very visual image is of the unnamed photographer capturing an image of a European, framed by the elephant’s palanquin as he is about to take a photo. An interesting moment as photographer perceives photographer. Elephants contributed to the logging operations of the Danish East Asiatic company and many photos record their vital involvement. One image records two elephants rolling a teak log in preparation for floating down the river.

Another image shows elephants working … ounging … the timber. The word of Burmese origin refers to the process of accompanying the logs in their descent from the river by pushing them through the water.

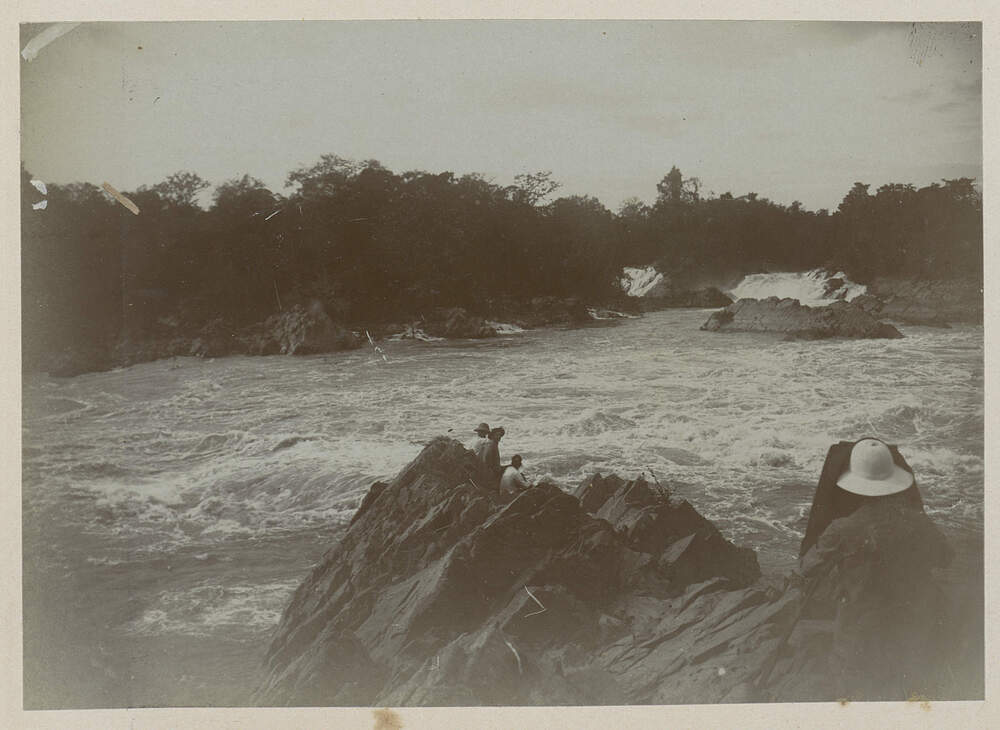

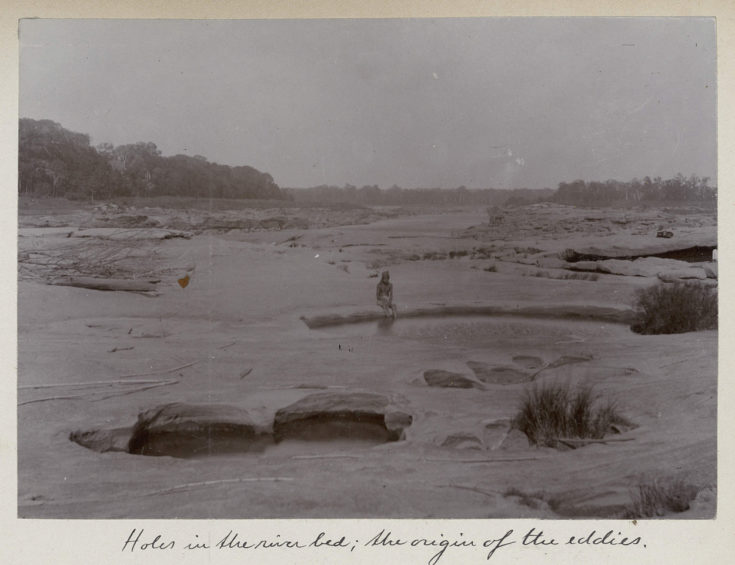

Some most exciting scenes are available as the travellers begin the long descent of the Mekong. Gunboats and steamboats attract the gaze of the photographer; the ‘LaGrandiere’ which served on the Mekong between 1893 and 1910, when it accidentally sank. Views also of the ‘La Garcerie’ and ‘Trentinian’, the latter being boarded by the travellers for part of their river journey. Especially powerful are the views of impressive natural landscapes and the rapids downstream of Khemmarat. About thirty photos focus on this stunning area, nowadays called the “Grand Canyon” of Thailand with holes in the rock giving rise to miniature lakes. Thrilling images record towering cliffs, swirling eddies and all is movement surrounding the travellers’ houseboat.

The Khone Falls, forming part of the border between Laos and Cambodia engaged the photographer’s eye and captured powerful images of thundering white water.

Further areas of research remain and questions are still to be explored and answered. The photographer’s identity remains elusive as does how the album found its way to the Université Côte D’Azur Bibliothèques. ( Personal communication from the archivist). The temple camp scenario piques interest as do the explicit connections between Danish East Asiatic and La Compagnie Est Asiatique Francaise travellers and a more precise dating of the trip. But for now, the little mermaid is safe in my keeping.

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the assistance of Dr Amnuayvit Thitbordin who directed me to the Danish East Asiatic photo album and whose 2016 thesis: ‘Control and Prosperity : The Teak Business in Siam 1880’s-1932 provided valuable primary research.

The Université Côte D’Azur Bibliothèques who hold the photo album in their collection and archivist, Antoine Hiemisch aided me in opening a window into the Danish East Asiatic Company’s history.

Anne C. Tan.

November,2021.

One Comment on “Travels in Siam and Laos: a lost photo album”