In this second article about the Norwegian explorer and scientist Carl Bock we follow his journey to the North of what is now Thailand.

Carl Bock left Bangkok the 9th of November 1881. A river steamer provided by the King took him to Nakhon Sawan, – Pak Nam Pho. Captain Andreas Richelieu of The Royal Thai Navy was in command, so our explorer was in professional hands. It took four days to cover the 250 kilometers. The ship did 6 miles per hour but the current mounted to 4.

The journey became monotonous and – unless you are a devoted botanicus – it really is. Your outlook from water level + 20 cm’s is limited to the banks of the river with their vegetation, maybe a croc now then, a village is passed. No horizon is visible. So, 6 miles forward but the current sets you 4 back; sometimes miles are longer than sometimes.

Years later, the railway reached Nakhon Sawan town where the waters, River Ping and River Nan with their tributaries meet. That happened in 1905 and from then on, miles were miles and the importance of the rivers started to decline.

North from Pak Nam Pho – and no money

When Bock arrived Pak Nam Pho, the comfort of the journey ended. He hired small boats and crew to take him up River Ping towards Chiang Mai and beyond. It was hard work from the beginning. The crews were not willing to travel north of their own district, new men were to be hired. Boats were lost in the cataracts and some of the men simply ran away.

Finally the strong and stubborn Mr. Bock reached the provincial town he calls ‘Raheng’, it must be the town and province today known as Tak.

Tak town, beautifully situated by the river, is approximately 360 kilometers NNW of Bangkok. It was then the real border town between Siamese and Lao territory and Carl Bock arrived up here the 10th of December 1881.

As mentioned in the first article published in December 2011, Bock was equipped with Letters of Introduction from the King and these still worked. He got a warm reception by the governor and was provided with 6 elephants for the journey onwards. Bock toured town and got impressed by the intense gambling, mostly with cards, here there and everywhere. Even children and grandmothers participated – a tradition well-known to this day.

It is a reliable sign of sovereignty that the country’s currency is accepted on the market. Although still – in principle – on Siamese soil; just a few kilometers north of Tak, around 20 o N. laterals, our traveler learned that the Ticals or Bahts of Siam were no longer current currency and could not be used. He was on Laotian territory. Here, only Rupees of British Burma were valid. This of course also caused trouble.

Furthermore the reception from the Laotian Princes along the route, although allied with Siam, became lukewarm even hostile. The small courts used the old tricks of holding him back for a period, for example by arranging prolonged parties or create ‘misunderstandings’ between him and some more or less noble. They undoubtedly wanted to show that they, not the Siamese King, had the power over this foreigners schedule and travel.

Chiang Mai and beyond

It would be much too extensive and beyond the scope of these articles to describe all Bocks writings about daily life and culture among the Laotian, Shan, Karen people north of Siam. Therefore only that he in the rather small but more developed principality of Chiang Mai established a fruitful contact with the Siamese Deputy Commissioner.

The commissioner himself had got himself so hated, that he had been called back to Bangkok. Many people came to Bock, expressing their grievances over him, especially over his ‘loose justice towards Laotians and Burmese people’, wanting only that a British Consul would be appointed. It should be noted that the Burmese were British subjects under British jurisdiction.

The Chiang Mai Royal House was ailing and the Siamese ready for a full take over. Officially the principality had been affiliated with Siam since 1774.

Of course also The American Mission was visited and Bock is well aware of the importance of this hastily expanding institution, especially in the field of providing medical care – although he suggests that the motives of the many sisters and nurses might not be totally altruistic but more “for ladies with whom, for instance, the course of love has not run smooth, and who are willing to seek solace in devoting themselves to a good work far away from the scene of their disappointments” (p. 223), a bit venomous our scientist can be.

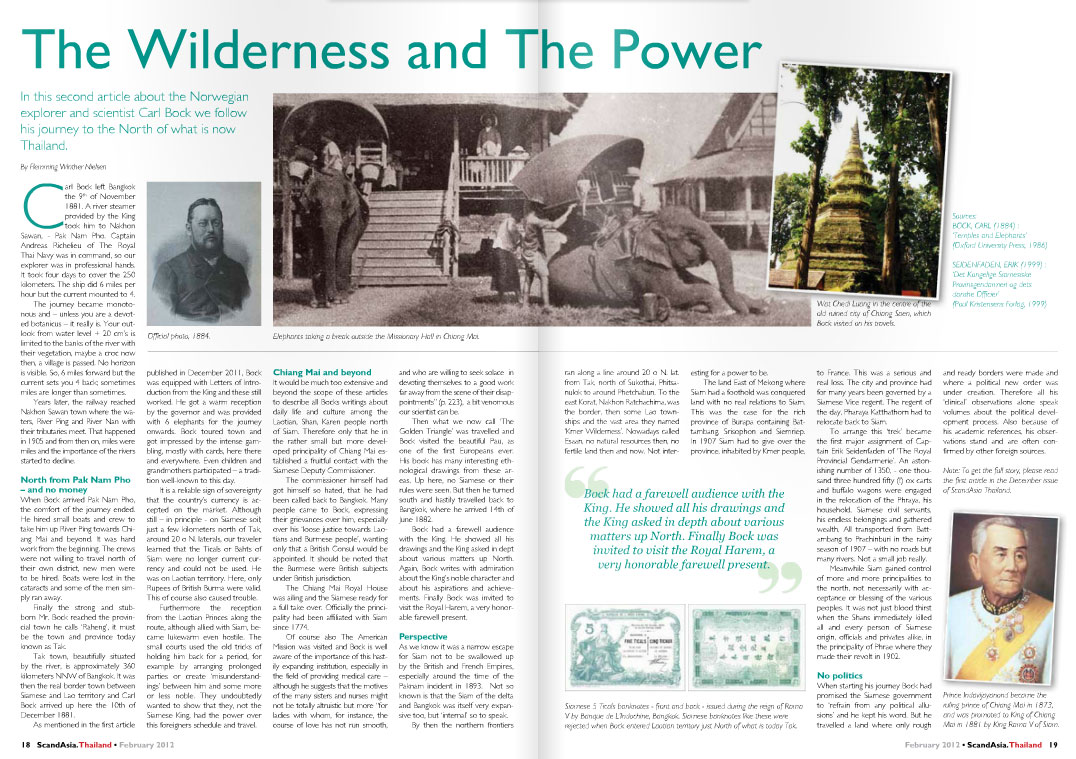

Then what we now call ‘The Golden Triangle’ was travelled and Bock visited the beautiful Pau, as one of the first Europeans ever. His book has many interesting ethnological drawings from these areas. Up here, no Siamese or their rules were seen. But then he turned south and hastily travelled back to Bangkok, where he arrived 14th of June 1882.

Bock had a farewell audience with the King. He showed all his drawings and the King asked in dept about various matters up North. Again, Bock writes with admiration about the King’s noble character and about his aspirations and achievements. Finally Bock was invited to visit the Royal Harem, a very honorable farewell present.

Perspective

As we know it was a narrow escape for Siam not to be swallowed up by the British and French Empires, especially around the time of the Paknam incident in 1893. Not so known is that the Siam of the delta and Bangkok was itself very expansive too, but ‘internal’ so to speak.

By then the northern frontiers ran along a line around 20 o N. lat. from Tak, north of Sukothai, Phitsanulok to around Phetchabun. To the east Korat, Nakhon Ratchachima, was the border, then some Lao townships and the vast area they named ‘Kmer Wilderness’. Nowadays called Esaan, no natural resources then, no fertile land then and now. Not interesting for a power to be.

The land East of Mekong where Siam had a foothold was conquered land with no real relations to Siam.This was the case for the rich province of Burapa containing Battambang, Srisophon and Siemriep. In 1907 Siam had to give over the province, inhabited by Kmer people, to France. This was a serious and real loss. The city and province had for many years been governed by a Siamese Vice regent. The regent of the day, Pharaya Katthathorn had to relocate back to Siam.

To arrange this ‘trek’ became the first major assignment of Captain Erik Seidenfaden of ‘The Royal Provincial Gendarmerie’. An astonishing number of 1350, – one thousand three hundred fifty (!) ox carts and buffalo wagons were engaged in the relocation of the Phraya, his household, Siamese civil servants, his endless belongings and gathered wealth. All transported from Battambang to Prachinburi in the rainy season of 1907 – with no roads but many rivers. Not a small job really.

Meanwhile Siam gained control of more and more principalities to the north, not necessarily with acceptance or blessing of the various peoples. It was not just blood thirst when the Shans immediately killed all and every person of Siamese origin, officials and privates alike, in the principality of Phrae where they made their revolt in 1902.

No politics

When starting his journey Bock had promised the Siamese government to ‘refrain from any political allusions’ and he kept his word. But he travelled a land where only rough and ready borders were made and where a political new order was under creation. Therefore all his ‘clinical’ observations alone speak volumes about the political development process. Also because of his academic references, his observations stand and are often confirmed by other foreign sources.