The future of Cambodian farmers is unknown. The country’s political situation is extremely unpredictable and so is the weather. Illegal logging of the forests contributes to climate changes and the farmers’ crops are lost. A small network of forest activists fight to protect the forest against the loggers, but it is not an easy job to face an enemy with no face.

A slightly green light reflects on the faces around the table. There is no air-con in this room, only a few fans, and today is a hot day. 34 degrees centigrade and humid as always. Despite the heat, they all wear long-sleeved shirts and trousers. Three of them even wear scarfs, and I cannot decide if that is for fashion or to keep warm.

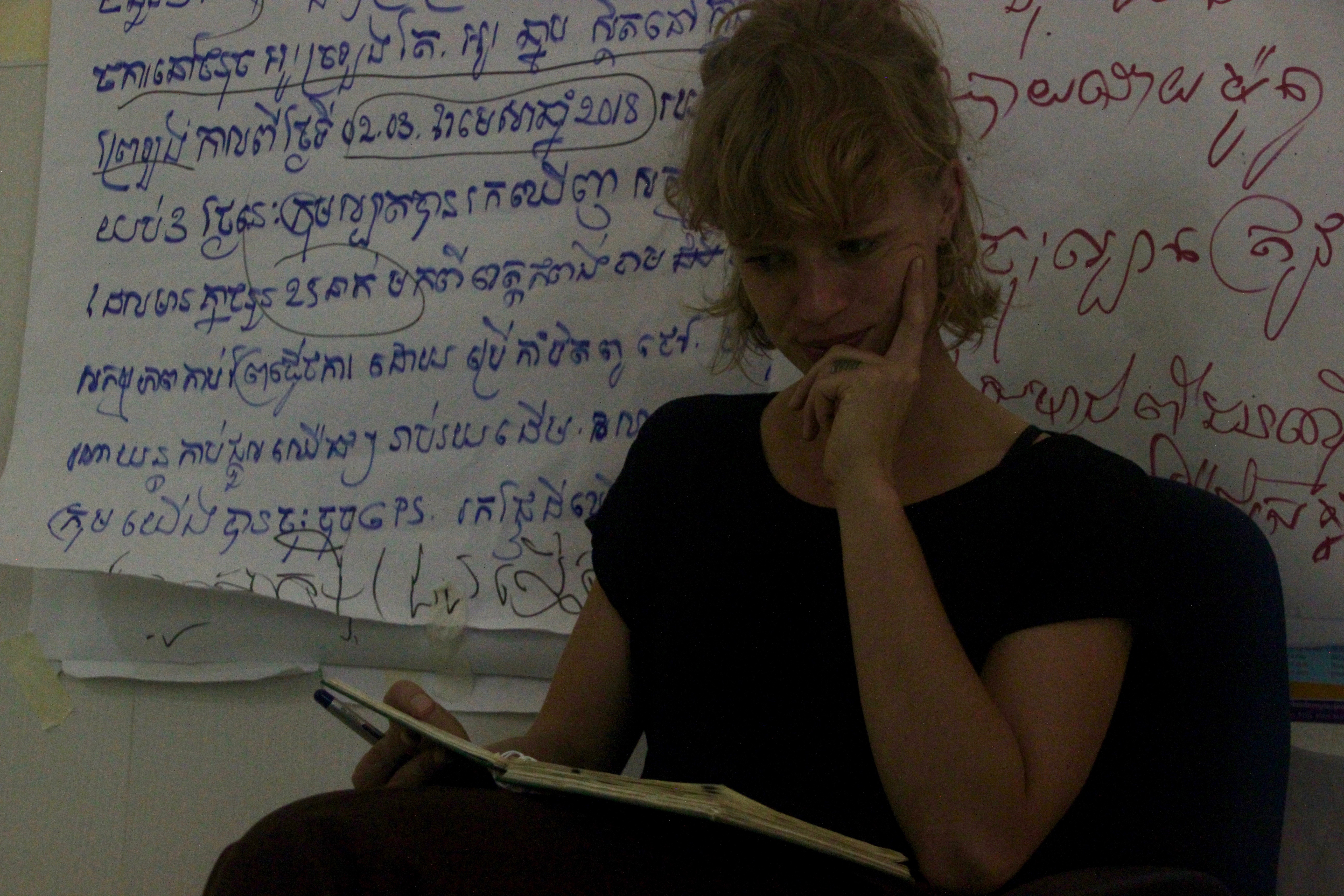

“What would you do, if you had just had an interview,” asks the only woman in the room besides me. She too is tall and blond, like me, classic Scandinavian.

The twelve men around the table are concentrated, some are taking notes and one man is filming the entire session. They are all farmers, but most importantly forest activists, here to do a two-day workshop on citizen journalism at the Danish NGO Danmission’s premises. The men are members of Prey Lang Community Network (PLCN), and the objective of the group is to document and stop illegal logging of the Prey Lang Forest. The project is called “It’s Our Forest Too”. A man in the back of the room, wearing a red shirt, answers in Khmer and a young, local man translates to English.

“But would you just post the interview as it is, or would you edit it in any way before,” the woman asks, and the man translates.

The young, local man’s daily work centers on the defence of freedom of expression and information. He and the woman, Danish Majken Søgaard, are doing the workshops together. The workshop is a part of the “It’s Our Forest Too”-project, in which Danmission takes part.

The farmers deeply depend on the forest

Some of the farmers have travelled quite some way to get here today. They come from four provinces, in which daily life depends on the crops that grow around the Prey Lang Forest. But the forest is threatened by illegal logging, making the farmers’ livelihoods endangered.

“We have always benefitted from the forest, and the people depend on the resources. We also have to keep the next generation in mind. We feel the climate change from day to day when you are farming, – the weather is changing, it is getting hotter and rain season is more violent than before. Everything becomes flooded, because of deforestation. The forest used to function as a filter,” Heoun Sopheap explains.

He is a fit man in his fifties and a prominent activist. In Cambodia, the forest activism is not greatly appreciated, and both the activists and the NGOs supporting the activism receive threats for their work. The price for cut down tree is high, making logging a tempting business. Especially in a country where people struggle to make a living. But it is not certain from where or who the threats are coming. I ask Heoun Sopheap if he has ever received any threats himself, and this is the only time I see him smile.

“More than you would know,” Heoun Sopheap states.

The fight against illegal logging

One to three times a month the farmers go on patrol in the Prey Lang Forest to find, confront and stop illegal loggers. But the patrols are extremely risky because of the resistance to forest activism. Heoun Sopheap himself has been facing a home-made gun, powerful enough to take down an elephant. And two years ago, a man attempted to murder a female activist with an axe while she was sleeping.

“He probably went for her head, but it was dark so he could not tell up from down, and ended up chopping her ankle,” explains Ernst Jürgensen, who heads Danmission in Cambodia.

The hazardous situations the activists find themselves in, makes conflict management a key element in the project. The farmers are educated in non-violent communication. And this seems to be working quite effectively. One time a group of only five activists encountered with nine loggers, who had four chainsaws. But through dialogue the activists convinced the loggers to turn over the chainsaws.

“Before the conflict management training the activists used to be more aggressive in their approach, because they held so much anger towards the loggers,” Ernst Jürgensen explains.

On this workshop, they learn how to use a specially designed app to make video documentation, interviews and small news articles – citizen journalism. It appears that journalistic work done by the activists reaches further than the work done by journalists. And it can be difficult for journalists to even visit the Pres Lang Forest – and so, the farmers have to do the media coverage themselves. And media coverage of the illegal logging is essential if they want to make political changes.

Governmental law enforcement is necessary

Two years into the project, in 2016, it finally caught the government’s attention. Ernst Jürgensen was invited to join a meeting. But only few were allowed to speak during the meeting – all of them supporters of the government, all of them claiming the illegal loggers are local villagers, who need the revenue from the sale of the harvested wood. But according to Ernst Jürgensen and the farmers, that is not the case.

“The loggers are outsiders, we do not know them,” states Kuy Chhoaw, one of the youngest activists at only 20, who has been going on patrol for two years now.

The future is unknown

A lot has changed since the project started, and the activists are now considered important players in the environment protection. The project is world-wide recognized, but there is still an urgent need for change. Young farmers do not know what future to expect, and for some the only way to survive will be to migrate to Thailand. The farmers who choose to stay are taught new cultivation methods. But at the moment it seems like a new method is needed every few months due to the rapid changes.

“The government need to take a responsibility,” Ernst Jürgensen states.

Until that happens, no one knows what future Cambodia is facing. And when I ask the young Kuy Chhoaw about his future, he laughs and looks down at his feet.

“I have no thing in mind. I will do agricultural work like my family,” Kuy Chhoaw states.

“Do you want to?”

“No, I do not want it, I just do not have a choice.”