In June 1881 the Norwegian explorer and scientist Carl Bock sailed up Chao Phraya River on board the steamship ‘Kongsee’ from Singapore. The ship passed the newly constructed and impressive Samut Chedi in Paknam, Samut Phrakan. The Chedi is sitting on the western bank of the river, a few kilometres north of Chulachomklao fortress.

Bock writes:

“I felt that I was at last in the land of Temples and Elephants, the land where sober truth and strange fiction are so curiously interwoven that it is often difficult to distinguish the one from the other”.

I will return to this statement in a moment, but why was he there, on the river, that day in June 1881, bound for Bangkok?

The years around 1860 to 1900 were the period of British Imperial explorations in Africa and Asia, with David Livingstone and Cecil Rhodes as the best known travelers.

In 1881 Bock was 32 years old and ready for an expedition lasting more than 14 month to the interior of Siam where he reached as far north as, what is now called, ‘The Golden Triangle’. His official mission was to gather mainly botanical and zoological specimens but also historical, cultural artifacts. He had studied Natural History in London for some years and was backed by ‘The Zoological Society’ there. Furthermore he was backed and financially supported by the Scottish Marquis of Tweeddale, William M. Haye, who himself was an enthusiastic botanist.

Carl Bock already had experience. He travelled Borneo in 1878, collecting specimens but also visiting and observing the native Dyak people -the headhunters- there. Shortly after returning to England he published ‘The Head-Hunters of Borneo’. Although an academic work the book became most popular and sold very well for many years; it is still available.

Back from Siam he published his new facts and findings in: ‘Temples and Elephants’ – ‘Travels in Siam in 1881-1882’ (Samson Low, 1884. Oxford University Press, 1986, still available). Also this work is composed along the rules of an academic natural science dissertation, including sober observations, provable facts and significant findings. But somehow, under the dryness, the descriptions of his many encounters with people and elephants become humoristic, funny and often most revealing regarding the mixture of truth and fiction.

At the special request of the Siamese Government Bock was asked “to refrain from any political allusions”. On the surface he is loyal towards this request, but lifted up one level you indirectly learn about the political machinery of the country; truth and fiction, pomp and circumstance. Also about, what we would name, propaganda, copied European lifestyle, norms and uniforms – whether deliberate or not, we get an extraordinary insight into Siamese domestic and foreign affairs revolving around the King.

As a first illustration of all this, I will soon let Bock describe the results of his meeting with a newly captured Royal White Elephant.

The not so white Elephant

On his arrival in Bangkok, Carl Bock had a very fruitful audience with king Chulalongkorn. Bock was equipped with Letters of Recommendations from the right people in London – and the king appreciated significant names of the best breed. Therefore ‘The Naturalist’ as he was named, was given a royal letter ordering all and everybody to facilitate him on his journey; alas, it didn’t always work up there in the North, where the royal jurisdiction hardly reached.

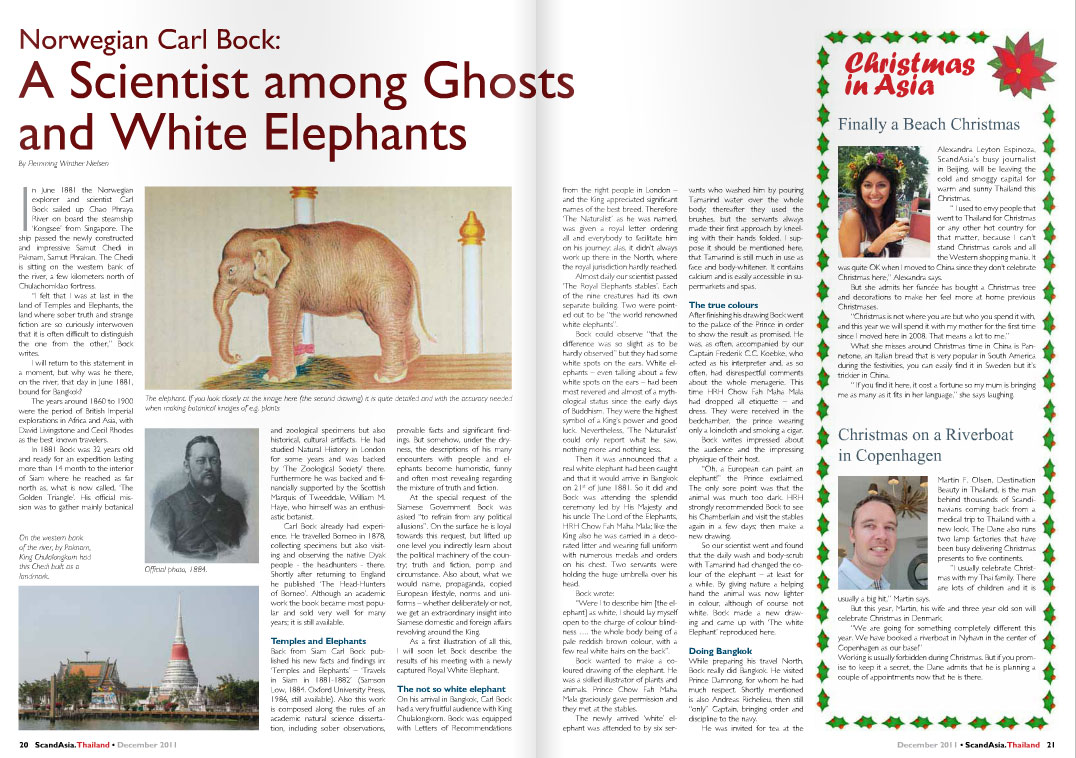

Almost daily our scientist passed ‘The Royal Elephants stables’. Each of the nine creatures had its own separate building. Two were pointed out to be “the world renowned white elephants”.

Bock could observe “that the difference was so slight as to be hardly observed” but they had some white spots on the ears. White elephants – even talking about a few white spots on the ears- had been most revered and almost of a mythological status since the early days of Buddhism. They were the highest symbol of a King’s power and good luck. Nevertheless, ‘The Naturalist’ could only report what he saw, nothing more and nothing less.

Then it was announced that a real white elephant had been caught and that it would arrive in Bangkok on 21st of June 1881. So it did and Bock was attending the splendid ceremony led by His Majesty and his uncle The Lord of the Elephants, HRH Chow Fah Maha Mala; like the King also he was carried in a splendid decorated litter and wearing full uniform with numerous medals and orders on his chest. Two servants were holding the huge umbrella over his head. Bock:

“Were I to describe him [the elephant] as white, I should lay myself open to the charge of colour blindness …. the whole body being of a pale reddish brown colour, with a few real white hairs on the back”.

Bock wanted to make a coloured drawing of the elephant. He was a skilled illustrator of plants and animals. Prince Chow Fah Maha Mala graciously gave permission and they met at the stables. The newly arrived ‘white’ elephant was attended to by six servants who washed him by pouring Tamarind water over the whole body; thereafter they used the brushes, but the servants always made their first approach by kneeling with their hands folded. I suppose it should be mentioned here, that Tamarind is still much in use as face and body-whitener. It contains calcium and is easily accessible in supermarkets and spas.

The true colours

After finishing his drawing Bock went to the palace of the Prince in order to show the result as promised. He was, as often, accompanied by our Captain Frederik C.C. Koebke, who acted as his interpreter and, as so often, had disrespectful comments about the whole menagerie. This time HRH Chow Fah Maha Mala had dropped all etiquette -and dress. They were received in the bedchamber, the prince wearing only a loincloth and smoking a cigar.

Bock writes impressed about the audience and the impressing physique of their host.

“Oh, a European can paint an elephant” the Prince exclaimed. The only sore point was that the animal was much too dark. HRH strongly recommended Bock to see his Chamberlain and visit the stables again in a few days; then make a new drawing.

So our scientist went and found that the daily wash and body-scrub with Tamarind had changed the colour of the elephant – at least for a while. By giving nature a helping hand the animal was now lighter in colour, although of course not white. Bock made a new drawing and came up with ‘The white Elephant’ reproduced here.

Doing Bangkok

While preparing his travel North, Bock really did Bangkok. He visited Prince Damrong, for whom he had much respect. Shortly mentioned is also, then Captain, Andreas Richelieu –bringing order and discipline to the navy.

He was invited for tea at the palace of the Wangna – the Second King. He was normally referred to as ‘George’ after George Washington, whom his late father had admired much. It seems that he did not participate in politics, but was a real student of minerals and had an impressive collection.

Young Carl Bock was not only invited for tea but also to visit the Wangnas harem. After a serious attempt of counting, it had earlier showed that Wangna had 54 wives. The promise was kept, but in the ladies rooms were only present the most senior generation of wives. Our scientist had a long cordial conversation with the Wangnas mother who was also present – and there the tea party ended.

The most dreadful and sickening experience for Bock was attending the ‘funerals’ of poor people. As usual he is most detailed in his description of how the dead body is just thrown on the dedicated spot on the ground. A few prayers and then a ’Butcher’ “cut the body open, with a long slash down the stomach”.

The vultures, carrion-crows and finally the dogs had waited impatiently. Now they immediately started their feast, the vultures first in line.

“Two birds, I noticed, at once picked the eyes out of the dead man, which had remained open all the while, adding to the ghastliness of the spectacle: whether the birds did this from fear or because they regarded them as a dainty, I cannot say, but they always make a point of picking out the eyes first”.

And Bock writes on, systematic and serious, page after page, but for once his language is marked by adjectives.

Not politics of course, but shortly after Bock published his book, these gruesome ‘events’ were forbidden and abandoned.

After such archaic experiences Bock was relieved to leave the town behind and embark on a houseboat sailing upstream.

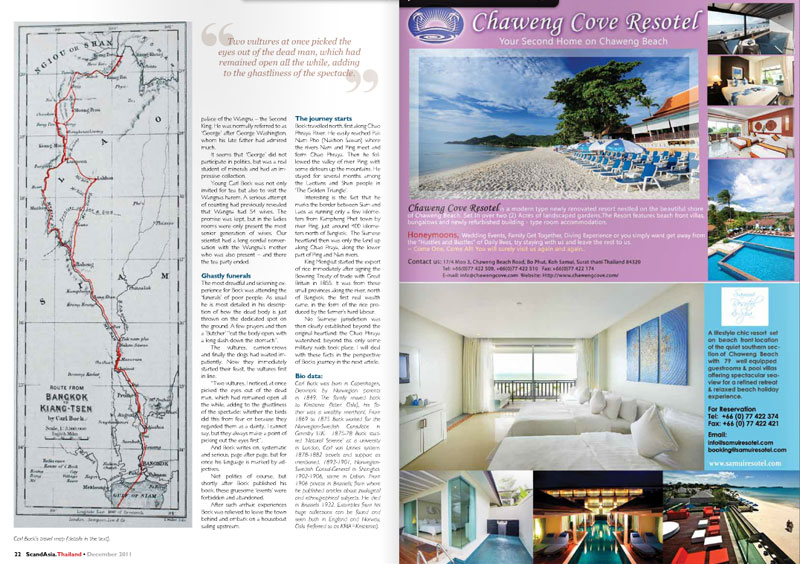

The journey starts

Bock travelled north, first along Chao Phraya River. He easily reached Pak Nam Pho (Nakhon Sawan) where the rivers Nam and Ping meet and form Chao Phraya. Then he followed the valley of river Ping; with some detours up the mountains. He stayed for several months among the Laotians and Shan people in ‘The Golden Triangle’.

Interesting is the fact that he marks the border between Siam and Laos as running only a few kilometers from Kampheng Phet town by river Ping, just around 400 kilometers north of Bangkok. The Siamese heartland then was only the land up along Chao Praya, along the lower part of Ping and Nan rivers.

King Mongkut started the export of rice immediately after signing the Bowring Treaty of trade with Great Britain in 1855. It was from these small provinces along the river, north of Bangkok, the first real wealth came, in the form of the rice produced by the farmer’s hard labour.

No Siamese jurisdiction was then clearly established beyond the original heartland: the Chao Phraya watershed; beyond this only some military raids took place. I will deal with these facts in the perspective of Bocks journey in the next article.

———————————–

Fact Box

Carl Bock was born in Copenhagen, Denmark by Norwegian parents in 1849. The family moved back to Kristiania (later: Oslo), his father was a wealthy merchant. From 1869 to 1875 Bock worked for the Norwegian-Swedish Consulate in Grimsby U.K. 1875-78 Bock studied ‘Natural Science’ at a university in London, Carl von Linnes system. 1878-1882 travels and support as mentioned. 1893-1901, Norwegian-Swedish Consul-General in Shanghai. 1902-1906, same in Lisbon. From 1906 private in Brussels; from where he published articles about zoological and ethnographical subjects. He died in Brussels 1932. Examples from his huge collections can be found and seen both in England and Norway, Oslo (referred to as KRIA=Kristiania).