It’s been more than seven years since Myanmar opened up to the rest of the world, leading to growth in business. The emerging country however still has major issues when it comes to suitability for foreign businesses.

The world was hopeful. Myanmar would not only open up to the world but also begin the liberalization of an economy that had been mostly isolated for more than 50 years. Foreign investors were eager to dive into the almost untouched market, the new Southeast Asian frontier, and quickly the planes were filled with businessmen flocking to Yangon and Naypyidaw to see what the country had to offer.

So now, seven years after the initial gold-rush, how has it actually turned out? Has it turned into the blooming economy like Vietnam or a corruption-ridden, pro forma-democracy, ravaged by civil wars and ethnic cleansing?

In this article we go through some of the main points that the Scandinavian business community makes when discussing the current business climate in Myanmar; the ups, the downs, the immature market, the lack of infrastructure, corruption and crises.

A developing country

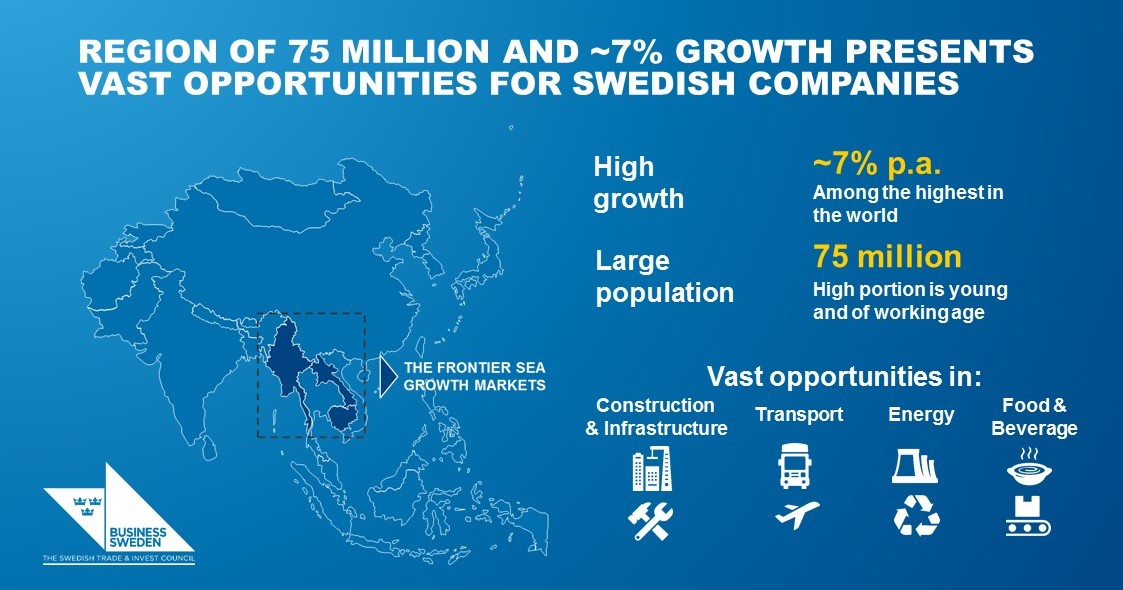

The first thing to take into account when analysing the market in Myanmar is the growing economy. In 2016 the GDP rose by 6,1 per cent and according to the IMF it is expected to grow by 7,6 per cent in 2018. The liberalisation of the economy as well as several business friendly laws has, to some extent, attracted foreign businesses.

And a few things have characterized the recent years’ development in Myanmar, according to a recently released report by Business Sweden: The laws are more accepting of foreign investors, the amount of mobile users has risen from 0.25% in 2005 to more than 80% in 2017 and it is currently shifting from an agricultural country into light industrialization.

On the other hand corruption is still very much an issue. Business Sweden has highlighted this as one of the biggest difficulties for companies when entering Southeast Asia.

Furthermore crucial parts of the infrastructure is lacking, with a low rate of electricity and frequent outages, a transportation system that the Asian Development Bank (ADB) predicted would cost US$ 45-60B in investments towards 2030 to upgrade to modern standards and a problematic financial sector.

These are some of the challenges that Myanmar faces on the way to becoming what Business Sweden described as a potential trade hub.

Somewhat optimistic business community

When consulting the Scandinavian business community in Myanmar’s views, the mood is generally hopeful, if not to say optimistic.

Vivianne Gillman is Sweden’s Trade Commissioner to Thailand and Vietnam, also covering Myanmar. When asked about the current business climate in Myanmar, she focuses on the development since the liberalization of the country in 2010/2011: “If you look at the general growth, it has developed exponentially since the liberalisation, making it one of the world’s fastest growing markets,” Vivianne Gillman says.

Vivianne Gillman is Sweden’s Trade Commissioner to Thailand and Vietnam, also covering Myanmar. When asked about the current business climate in Myanmar, she focuses on the development since the liberalization of the country in 2010/2011: “If you look at the general growth, it has developed exponentially since the liberalisation, making it one of the world’s fastest growing markets,” Vivianne Gillman says.

“This is something that can be seen in different types of infrastructure investments; building roads, setting up industries, building the cities’ transportation systems, energy, water and more. The country is now being rebuilt in terms of getting the basic infrastructure in place,” she says.

And that optimism generally carries throughout the community. Andreas Sigurdsson is the Managing Director at Lychee Ventures which specializes in the start-up industry of Myanmar. He, just like Vivianne, is generally positive about the development of the country: “I would describe the current business climate as better than before. Laws are improving and better facilities are accessible such as fibre internet and local data services. There are more business services established so you can get better support to,” he says.

A most immature market

But even though Myanmar may be developing and growing, it is not nearly out of the woods yet. As the economy grows and the country shifts into the early stages of industrialization, through for example the garment industry (H&M has been sourcing to Myanmar since 2014), the expansion of the necessary infrastructure is very much needed: “One of the main challenges we see is the lack of proper infrastructure like energy and transportation. Even shipping your products out of Myanmar can be a logistic challenge and very costly,” Vivianne says and adds that “as the industrialization continues, this is improving.”

But for now it is still in the early stages, dependent on support from other countries and from multilateral development banks: “Myanmar is still on the lowest step of the maturity ladder. Currently the strive is to move Myanmar from the agricultural state and into early industrialization, mostly through investments from China and Japan, but also through organizations such as the Asian Development Bank and The World Bank,” she thinks.

Localizing and keeping talents

Martin Hamann is a Danish independent market consultant based in Myanmar, who earlier headed a solar energy company. According to him, one of the main issues a company faces when working in Myanmar is acquiring competent work forces and retain them.

“One of the things we struggle with in Myanmar is to find the talented workforce. People who studied abroad are very valuable on the market, which makes the transition rate very high as of now,” Martin Hamann says.

“But it is not only the highly trained workforce. Even common jobs that require English and basic skills in Excel to manage a warehouse or coordinate marketing can be hard to find applicants for,” he says.

So often you hire a head hunter, someone who knows the business community and have a knack of locating the employees a company needs. But the high demand for skilled labour makes it difficult to keep the workers once you finally found them: “There is a very high demand for talented workers and they can be scarce, so head hunters can be the key to find the best suited person for the task you have. But even then it is not certain that he or she won’t move to another job within the first year. There is a very high transition rate at the moment,” he says.

Financial infrastructure run by cronies

Something multinational businesses take into account when considering whether to open a branch in a new country is how convenient it is to actually do so; how the process of applications, permits and financial requirements are and how the local judicial system is set up for foreign investors.

And it does not look good for Myanmar: in the most recent annual ‘Ease of Doing Business’ report was released by The World Bank. Myanmar still ranks as one of the lowest countries in the report (and in the lowest in the region), as the 171st easiest country to do business in, dropping one spot since 2017.

Part of this is the financial infrastructure; how the processes are when applying for loans, how open the country is for investors and whether the banks are actually trustworthy or not when it comes to doing business.

Bertil Lintner is what you would call a veteran journalist in the area. Since the beginning of the 80s he has been present in Myanmar and Southeast Asia and he doesn’t hold much optimism when it comes to the country actually moving very much forward: “The first thing Vietnam did when they opened up, and this was very clever, was to allow foreign banks to enter the market. This drew international investors to Vietnam and the country has flourished since,” Bertil Lintner says.

“Burma didn’t do that. What they did instead was monopolizing the market with Mickey Mouse-banks run by local cronies, and this affects foreign investors. That is Burma’s biggest financial problem; not the government, ot the Rohingyan crisis or the civil wars, it’s that the financial infrastructure just isn’t there.”

In general he doesn’t believe in the optimism that’s shown by the rest of the community: “Just take a look at Yangon. The hotel prices are shrinking, the planes are half empty; the investors turned away,” he says. ”The west started considering sanctions against Burma soon after the country opened up. Naturally, this drew investors away; nobody wants to get involved in that.”

“Some western companies are here, but the major investments do not come from the west. They come through loans from China which is slowly re-gaining power over Burma,” Bertil Lintner says.

The Chinese influence

One of the major topics that Bertil Lintner has covered over the past decade is the Chinese buyout of Myanmar: “We saw it with Sri Lanka. To build basic infrastructure like ports and roads, they took loans from China. When they weren’t able to pay those loans back, China took over, and it’s important to note that is has been a long-lasting plan for the inland empire to gain access to the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean,” Bertil Lintner says.

China’s coastline is very limited in terms of accessing the markets to the west; their only coastal line faces towards the Pacific Ocean, so it would mean great growth for China if a proper shipping line through the Indian Ocean could be established.

And according to Bertil Lintner, that is currently on the verge of happening in Myanmar. The country is in desperate need of a better infrastructure and the Western investors are hesitant, so China steps in. And it’s not only in transportation and logistics.

“The local banks owe millions of dollars to China and they can’t pay them back. To a large extent this gives China the power the banks and the loans provided by them. China is basically buying Burma at the moment,” says the Swedish journalist.

The humanitarian crisis

The on-going conflicts in the country are of natural concern for a large multinational company. Speaking from a PR or a CSR perspective it is seldom very attractive to be supporting a government carrying out what the UN has described as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing” as in the case with the Rohingyan minority.

According to Vivianne Gillman at Business Sweden, the situation may deter certain companies that were on the verge of entering the country: “It creates caution among the businesses. Those already in Myanmar will most likely carry on, sometimes with greater caution. Regarding companies contemplating to enter the market we know that some still chose to enter now while others wait.”

And the Rohingyan crisis brought further sanctions on Myanmar, although they in most cases didn’t touch any of the products that Scandinavian companies (except for Sweden) would be interested in. The free and open market still stands, but the EU implemented sanctions towards dealing arms with the country – the ‘Everything But Arms’ sanctions.

Corruption is a factor

A subject often arising when discussing business in Southeast Asia, is the corruption. Some say it’s an inherited part of the culture while others will argue that it’s only exists as long as the authorities allow it. Nevertheless, corruption is not an uncommon practice as part of the political day-to-day life in Myanmar.

According to Vivianne Gillman corruption is something a company should be aware of when doing business in the market: “Most Swedish companies with experience in the region knows that once you give in just a little bit to unethical behaviour, it becomes difficult to avoid in the future even if it was to just accelerate a process at the customs-agency.”

Best fields right now

Setting corruption, lack of infrastructure and the emerging Chinese aside, what are the solutions and products that Myanmar are seeking right now? Which areas are obvious for a Scandinavian company to cover if they want to enter the market?

The short answer is: there’s plenty! “The country is developing fast, so not getting involved is missing out on opportunities to make a difference. There are needs in pretty much all sectors such as infrastructure, energy, education, healthcare etc. I don’t see any changes in terms of investment in these areas,” says Andreas Sigurdsson.

So to round it up, Myanmar is in many ways a complicated country. Many things are needed before Myanmar can move further up the maturity ladder and become what many hoped would be the next trade hub and booming business market in Southeast Asia. But according to the business community, Nordic countries have a chance of becoming a part of this pull.